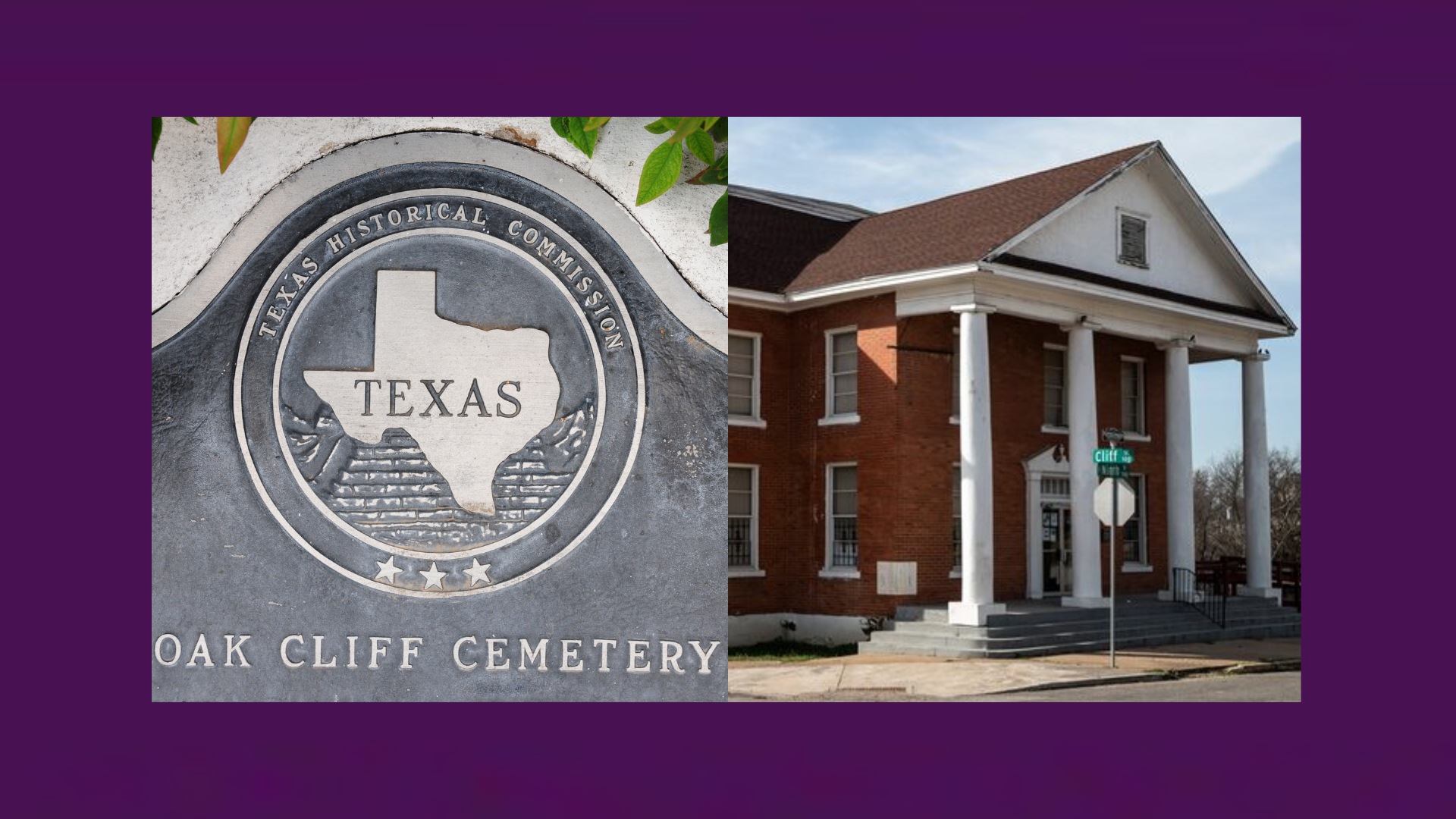

Sitting eerily close to our campus is the Oak Cliff Cemetery. I’ve wondered time and time again who would put an elementary school and a high school so close to a burial ground. What I should’ve been asking myself is what history lies within those gates. Last time, we dove into the thick history of the historic Tenth Street Freedman’s Town starting right across the street from our front doors. This time, we’re exploring further.

The Oak Cliff Cemetery is much more than the first public cemetery in Dallas; it holds the life tales of many black men, women, and children of the post-Civil War era. Shortly after the Battle of the Alamo, William S. Beatty moved to the Texan Republic and settled on 640 acres along the Trinity. On June 5th, 1846 he declared “ten acres more or less” to be used for burials. It was originally named Beaty Cemetery, and then Hord’s Ridge—after Judge William H. Hord—and after several decades, it was finally renamed ‘Oak Cliff Cemetery,’ as we know it.

Like we discussed last time, one of the most notable facts about the cemetery is the African American section. The southern part (away from our school) holds the graves of many enslaved peoples and freedmen.

This feature is an incredible reminder of the once segregated lives that Dallas residents—and most of The United States—lived. There are many notable people buried there. Sam Houston’s second to last son, Colonel William Rogers Houston, was buried there in 1920 following a fatal stroke in March of that year. Many former mayors, like John Kerfoot, George Sergeant, and George Sprague, were buried there. Leslie Stemmons—yes, like the freeway named in his honor—was buried there after an influential life as a prominent businessman. Noah Penn, who founded El Bethel Baptist Church, is among the noteworthy African Americans buried in the southern section.

Crazily enough, there are some even more interesting facts about the cemetery. For one, it seems to historians that nobody did genuine record-keeping until 1905, when Williem Merrick Miller Jr began a ledger and cards on the interred individuals of the cemetery. In the late 50s, Miller created a new ledger book, which was the only one out of the two to survive a fire that broke out in the 70s. Even crazier, technically no one owns Oak Cliff Cemetery. A Board of Trustees, all personally connected to people buried in the cemetery, governs the cemetery by using money from the trust fund established in 1955.

There are no more active burials in the cemetery, as it holds over 5,000 marked and unmarked graves, but beyond that, it possesses the stories of the lives of many, not unlike all other cemeteries.

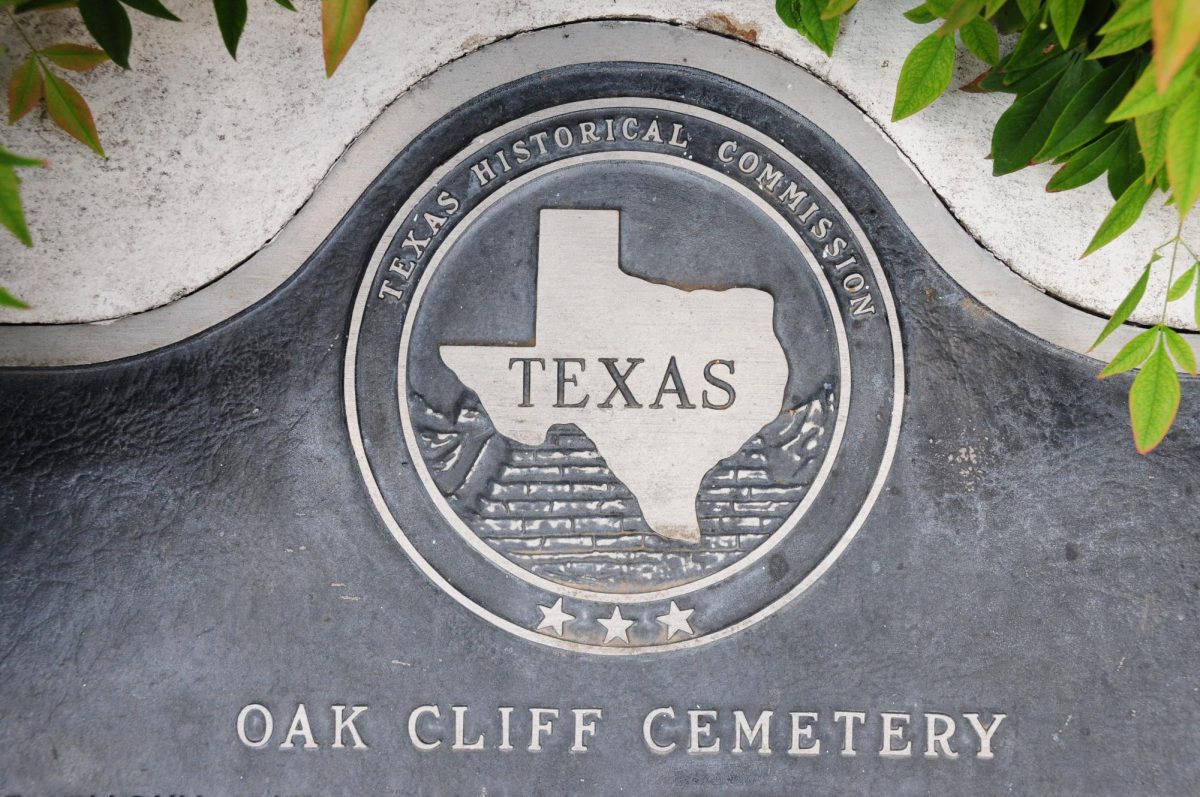

Like I mentioned earlier, Noah Penn, the founder of El Bethel Baptist Church, is buried in the cemetery, but let me tell you about the church itself. El Bethel Baptist Church was located on Tenth Street, and it was founded by the aforementioned Noah Penn, a trailblazer of Tenth Street. Following Emancipation, the formerly enslaved often established their own communities, fit with ‘negro schools and churches.’ Within said communities, the churches held the paramount role of guiding the spiritual and cultural senses of African American life at the time. They also stood as the principal economic and social resources for African Americans. Greater El Bethel Missionary Baptist Church had its beginnings in the mid-1800s; the congregation was home to many families who were diligent in helping build the Tenth Street community. These educators, developers, and leaders collaborated to scrape together funds to build churches and form aid societies for Freedmen.

In 1909, after having to move several times, the congregation began to work on a new building. They volunteered their time to dig out the basement with teams of mules and by hand and worshiped in the basement until the sacrarium was completed in 1926.

Rev. William L. Dickson became pastor at Greater El Bethel Missionary Baptist Church in 1926. He and his wife, Inez, set up a day nursery for African American working women and Rev. Dickson acted as a mediator for the Dallas community during an intense and unjust time of racism. Meetings were held at the church to counsel friendly interactions with the Anglo community. In the beginning of the 20th century, Tenth Street had one of the largest accumulation of churches per mile in the world. Now, only Greater El Bethel Missionary Baptist Church remains, and there are three branches of El Bethel, the other two residing outside Tenth Street. Today, Greater El Bethel Missionary Baptist Church continues to hold service, celebrating more than one hundred years of community through faith.